Ratatouille and the Arbitrary Essence

Part 6 of the series How to be yourself, with help from Disney/Pixar (Thinking about Identity and the Inner Voice)

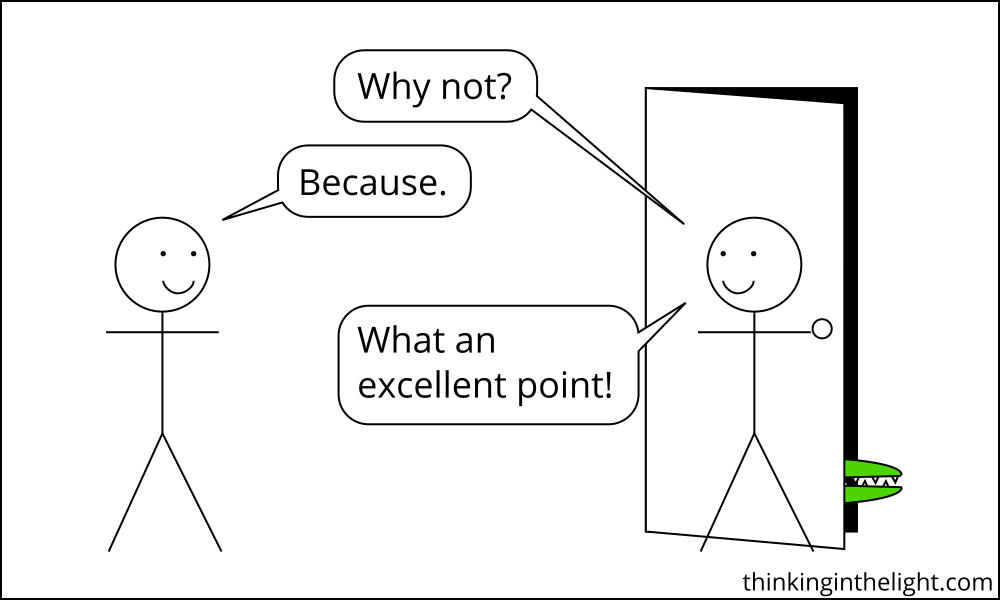

I don’t like being told what to do. I suspect that you don’t like it either. My children definitely don’t like being told to do things. At times we will grudgingly admit that a certain command was good. (Don’t open that door! Behind it is a congregation of alligators!) But what we really hate is when we want to do something and someone prohibits us for reasons that are arbitrary. When asking “Why can’t I do it?” everyone’s least favorite answer is “Because I told you so.”

Arbitrary prohibitions are the focus of the movie Ratatouille, and it doesn’t like them any more than you do. (Actually, it may like them even less, since you have never created a movie to express your dislike.) Being a Pixar movie, Ratatouille makes this point in an entertaining way, by means of a plot that sounds like it shouldn’t work but does. (Spoiler alert, in case you want your experience of its unusualness unspoiled.) It is a children’s movie set in the world of French cuisine, revolving around a will and a question of paternity, with villains who are a critic and a chef who is trying to erect a frozen foods empire. Also, a central character, Chef Gusteau, dies before the movie starts, but this doesn’t stop him from being in it. Pixar takes all of these elements and somehow makes them work.

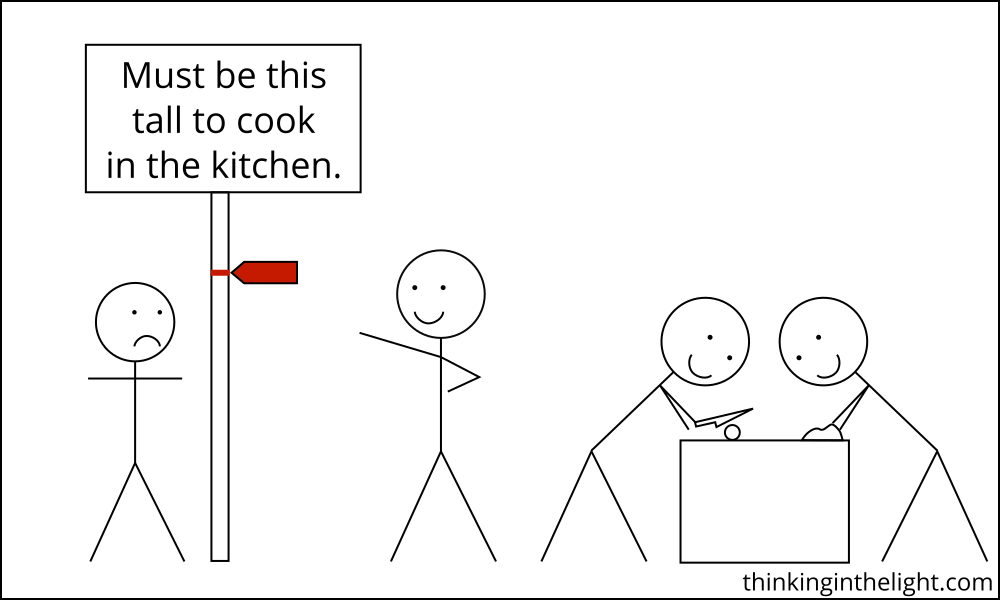

In Ratatouille, the arbitrary prohibitions in view are those that try to stop someone from entering their chosen profession. For example, these limitations are highlighted by the character Colette. She is a skilled chef, but this skill does not guarantee her a place in a kitchen, given the historical prejudice against women. She had to work extra hard to get to where she is.

How many women do you see in this kitchen? Only me. Why do you think that is? Because haute cuisine is an antiquated hierarchy built upon rules written by stupid, old men—rules designed to make it impossible to enter this world. But still I’m here! How did this happen? Because I am the toughest cook in this kitchen.

She has the skills and desire to be a chef, but she is nearly prevented from being one due to arbitrary limitations put in her way by others.

Another source of arbitrary limitation is the critic Anton Ego, who wrecks the career of Gusteau. Chef Gusteau had a thriving restaurant due to his talent, but Ego writes a devastating review of it, resulting in the restaurant losing a star from its five-star rating. Ego thrives on dishing out negative criticism, which he later admits “is fun to write and to read,” so the review likely did not reflect a true defect in Gusteau. It was an arbitrary exercise of the critic’s power that impacted Gusteau’s ability to be a chef.

This clash between Ego and Gusteau provides Ratatouille with the opportunity to make its message explicit. Chef Gusteau titles his cookbook Anyone Can Cook, while Ego declares, “No, I don’t think that anyone can do it.” When Gusteau clarifies the meaning of his title, he emphasizes that people shouldn’t let others limit them.

You must not let anyone define your limits because of where you come from. Your only limit is your soul. What I say is true, “anyone can cook,” but only the fearless can be great.

This fits with Colette’s story. She did not let others limit her but followed through on her abilities. Even Ego’s story concludes by making this point, since at the end of the movie he has learned his lesson. After he is surprised by a meal he is served and by the chef who cooked it, he finally agrees with Gusteau.

In the past, I have made no secret of my disdain for Chef Gusteau’s famous motto “Anyone can cook,” but I realize only now do I truly understand what he meant. Not everyone can become a great artist. But a great artist can come from anywhere.

This, then, is the message of the movie. We should not judge people for who we think they are, looking at their origin and dismissing them too soon—”She is just a woman.” To place such a limit upon them is arbitrary.

And as a message it is not a bad one. Clearly many women have suffered prejudice that has prevented them from fulfilling roles at which they would excel. The same could be said about people of other races from the dominant one, other religions, generations, and so on.

But this is not really what I want to focus on here. My interest is less in the message and more in how it is presented. The quotes above emphasize character traits like toughness and fearlessness, but this is not the central way Ratatouille presents its point. Instead, the focus of the movie is on identity. And now, having so far spent this whole post discussing various human characters in Ratatouille, it is time to point out that the main character is a rat.

Remy lays out his dilemma right at the beginning, as a way of introducing himself.

This is me. … What’s my problem? First of all, I’m a rat. And second, I have a highly developed sense of taste and smell.

When this dilemma is fleshed out, it becomes clear that it is an issue of essence versus the inner voice.

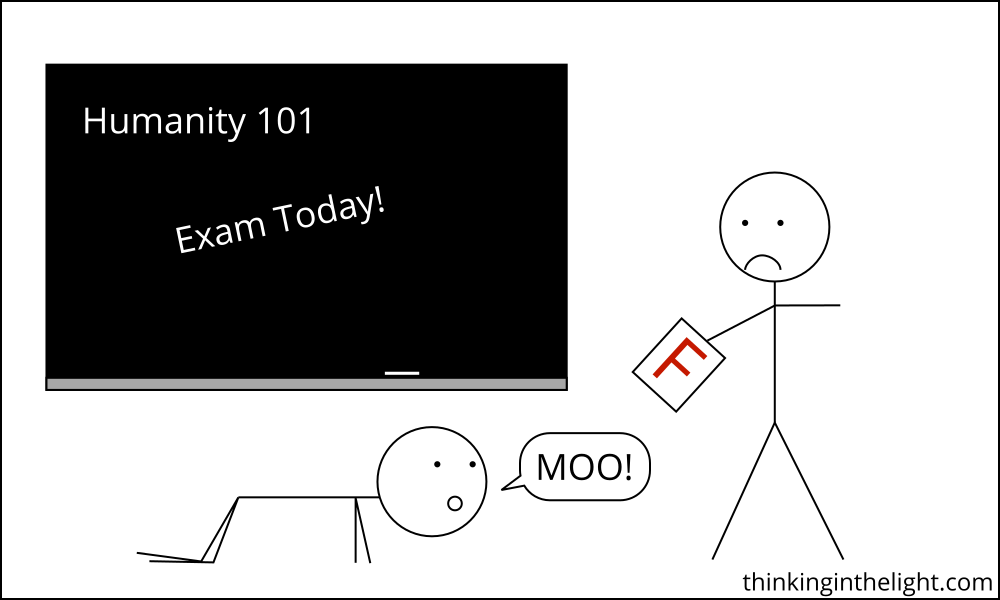

As I discussed in the previous post, an essence is that which defines something as the kind of thing it is. Your essence is that of a human, a living thing that can think, talk, and act morally. Remy’s essence is that of a rat, a scavenging animal that walks on all fours. And as I also discussed, our essence impacts what we should do. If I am a human, then I should behave like one.

Remy, however, does not want to behave like a rat. Because of his heightened senses of taste and smell, he sees his vocation as that of a chef. And this is traditionally an occupation for humans. While this vocation makes sense in light of Remy’s unique taste and smell, the justification for pursuing it arises, in large part, from some version of what this series has been exploring—the inner voice. In Ratatouille, Remy’s inner voice is represented by a dialogue between himself and an imaginary Chef Gusteau, and it is through these conversations that Remy embraces his vocation.

But in the movie, despite his skills and despite his desire, most of the other characters do not want Remy to embrace his chefness. This arbitrary prohibition comes from the fact that he is a rat. He has the passion and abilities to be a cook, but people think of rats as pests that shouldn’t be in a kitchen.

Remy’s dad is one of those who oppose Remy’s ambitions. He does so by emphasizing what Remy is, his essence.

Remy [explaining why he will be living with a human, not with the family of rats]: Eventually a bird’s got to leave the nest.

Dad: We’re not birds; we’re rats. We don’t leave our nests; we make them bigger.

Remy: Well, maybe I’m a different kind of rat.

Dad: Maybe you’re not a rat at all.

Remy: Maybe that’s a good thing.

Remy explains how he wants to stop taking food and create it instead, and his dad says this is talking like a human. In an attempt to change Remy’s mind, his dad shows him a storefront for an exterminator, a window filled with dead rats. He argues that given what rats and humans each are, this antagonism is inevitable. Remy objects.

Remy: No. Dad, I don’t believe it. You’re telling me that the future is—can only be—more of this?

Dad: This is the way things are. You can’t change nature.

Remy: Change is nature, Dad, the part that we can influence. And it starts when we decide. [Remy turns to leave.]

Dad: Where are you going?

Remy: With luck, forward.

Remy is resisting this idea that his essence matters when it comes to what he does, but soon he is reminded that humans do in fact see rats as “disgusting little creatures.” Even his human friend throws Remy out of the restaurant after he helps his rat family to steal food from it. At this point he stops resisting and concedes to his father.

Remy: You’re right, Dad. Who am I kidding? We are what we are, and we’re rats.

Here he despondently accepts his essence as a rat, but the turning point of his story comes when he embraces a different identity. He is captured by the scheming Chef Skinner, and while he is caged he has a conversation with the imaginary Chef Gusteau—that is, a conversation within his own mind.

Remy: I’m sick of pretending. I pretend to be a rat for my father. I pretend to be a human through Linguini [who helps Remy to cook food]. I pretend you exist so I have someone to talk to. You only tell me stuff I already know. I know who I am. Why do I need you to tell me? Why do I need to pretend?

Gusteau: Ah, but you don’t Remy. You never did. [Gusteau disappears.]

After this realization, Remy is freed by his dad and brothers, and he starts running back to the restaurant, declaring that they will fail without him. Remy’s dad asks why he cares. Remy responds by summarizing what he has just realized.

Because I’m a cook!

Remy returns to the restaurant, where he faces further discrimination, but he also triumphs by winning over Ego the critic with his cooking.

In this central story, then, Ratatouille presents its message about arbitrary limitations in terms of identity. People discriminate against Remy based on the fact that he is a rat, when the more salient identity is that he is a cook. The movie prioritizes Remy’s identity from the inner voice—it was literally found through a dialogue with a figment of his imagination—and it downplays any identity that would come from his essence. In fact, in using identity to make its point about arbitrary prohibitions, it makes essence look arbitrary. Just as Colette is a woman and people place limits upon her because she is not a man, Remy is a rat and people limit him just because he has a non-human essence.

And now, having so far spent this entire post explaining the message of Ratatouille, and having explained how the movie uses Remy’s story to make it, it is time to point out that this story is cheating. Essence isn’t arbitrary. I don’t want to take away from the movie’s point as I discussed it in the first part above; however, the way it makes this point in Remy’s case is problematic. It is arguing that, when it comes to my identity, my inner voice should win out over my essence. And it presents this view in a way that makes the idea sound plausible. Take, for example, the low point of his story, when the conniving Skinner traps Remy. Skinner looks at him, and with an evil sneer, he makes the exact opposite point from what Remy goes on to learn.

You might think you are a chef, but you are still only a rat.

As we are watching the movie, we feel this statement as nothing but a slight. It is explicit prejudice, given the fact that we have seen by this point how great of a chef Remy is. By discounting this and emphasizing Remy’s essence instead, we see Skinner’s malevolence laid bare.

But we feel this not because the movie is making a good point about essence. We feel it because Remy is not really a rat. Sure, he has fur and a tail, but given everything Remy can do—think, talk, make ethical decisions, cook—he is, through the magic of animation, a human that looks like a rat. That is, because Remy is an anthropomorphic rat, his essence is not truly that of a rat, but that of a human. This is what makes Skinner’s statement feel so horrible. He is arbitrarily limiting (and caging!) a small, furry human.

Picture instead if Remy couldn’t talk or read or cook. Picture him having the essence of a real rat. In that case, if Skinner looked at him in the cage and said, “You might think that you are a chef, but you are still only a rat,” it would be comedy. Remy would obviously be a rat, so it is funny that Skinner pretends he is plotting a career in fine cuisine.

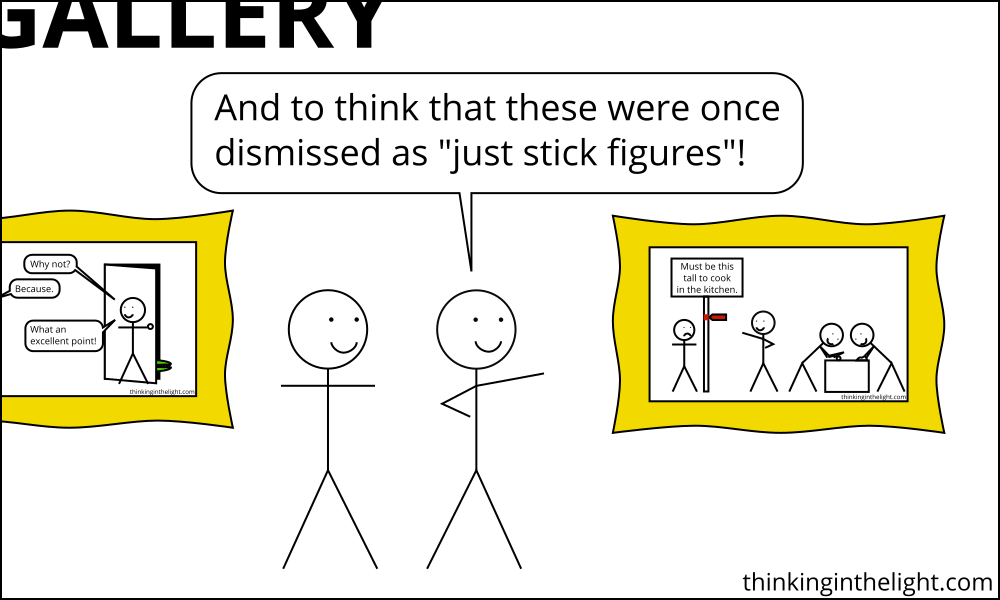

Ratatouille makes us feel that appealing to Remy’s essence is arbitrary when it comes to his identity and what he should do—that one’s inner voice should trump their essence. But we need to think carefully when it makes this point, since the movie equivocates on what Remy’s essence is, calling him a rat but making him a human.

Maybe this equivocation is innocent and arises simply from the fun convention of having talking animals. It could be that the movie isn’t really trying to make a point about essence but instead just wants to illustrate in a lively way the sort of discrimination that people like Colette face. (It is easier to get kids to watch a movie about rats than one about sexism.) If this is the case, then we just need to be aware of what the story is doing and the limits to how it is doing it.

On the other hand, it could deliberately be making the point that essence is arbitrary and the inner voice should prevail over it. This is a popular position to take in contemporary culture, so it would not be surprising. I once had a friend who told me that Ratatouille felt more modern than early Pixar films (such as Toy Story), and his statement was intended as praise. In my previous post on essence, I explained how Augustine is in favor of finding our identity in our essence. Augustine was a Christian bishop who lived many centuries ago, so it is not surprising that he would take this position. In general, it is an idea that fits better within an ancient or a Christian framework. While Augustine was both, contemporary American culture is neither—it loves the inner voice, saying that I determine who I am, not the culture or my family, and not even any supposedly essential qualities that are handed to me by my nature. As I argued in the previous post, I disagree with this contemporary view and side with Augustine. However, my point here is that even if the contemporary model is true, Ratatouille would not be a fair argument for it. The movie equivocates on Remy’s essence in a way that obscures the issue.

This series has been examining the notion of identity, and in particular how identity relates to the inner voice. Ratatouille and Moana make the inner voice the foundation of my identity. Pinocchio and Toy Story set aside the inner voice in favor of doing what is morally right, with the latter explaining this morality in terms of the identity provided by my essence. Frozen and its sequel both glamorize the inner voice while simultaneously depicting reasons to do the right thing instead, making their messages ambiguous. I hope that through looking at these movies I have successfully illustrated some of the issues we should think about when considering our identity and whether we should follow our inner voice. If so, I have achieved my goal for this series. There are many more facets of identity that could be discussed, but I’m going to stop here. It is time to switch gears and start a new series. And who knows, with this series done, maybe I’ll even attempt to watch an animated feature film without stopping afterwards to write an essay.

Share this post or sign up for future posts:

Bibliography:

- Ratatouille. Pixar Animation Studios, 2007.