Pinocchio and Striving to Become

Part 1 of the series How to be yourself, with help from Disney/Pixar (Thinking about Identity and the Inner Voice)

“Be yourself!” This advice is often given, and it seems like it ought to be the easiest advice possible to follow. If someone told me, “Be the CEO of a company,” that would take some work. If I was told, “Be a gold-medal-winning Olympic weightlifter,” that would be even harder. And if the advice was “Be a five-dimensional space turtle,” then my puzzlement would only be outweighed by the impossibility of the task.

But I have already achieved being me. … Or have I?

If I need to be told to be myself, this implies that there is a way in which I can fail at the task. And if this is the case, then we can ask further how I might fail or what it would look like to succeed. That is, we would need to address the topic of identity.

When I speak of my identity, I am speaking of the thing or things that define me. Who am I fundamentally? This matters, because it shapes what I do. If Maggie sees herself as primarily a CEO (that is, in terms of her job), then she will prioritize her work over other obligations. If everyone expects Max to be a Christian, but he sees his identity as being a Marxist, then he may decide to go against the wishes of his community, even if it costs him. How I view my identity shapes my life.

There is a lot that could be said about identity, but in this series I’m going to focus on a particular aspect of the issue: Do I find out who I am by looking inside myself or by looking to something outside of me? That is, do I follow my inner voice or do I heed an external call?

In order to think about these questions, I’m going to turn to the experts. Disney and Pixar have been exploring the issue of identity in their animated movies for years, so I will use several of these as examples. My goal is to make explicit the ideas that lie behind the stories and contrast their differing visions of what it means to be me.

In this first post I will begin by looking at Disney’s second animated feature, Pinocchio. I suppose I should issue a spoiler alert, since I will be discussing the details of the plot. But really, you’ve had 80 years to watch this movie, so it is your own fault if you haven’t. (And I guess the title of this post already gave away the ending, so whoops.)

Pinocchio is a high-point among Disney’s hand-drawn animated features. I did not fully appreciate it until I saw a documentary on the movie a few years ago, but the attention to detail in the drawings is amazing. As a story, on the other hand, Pinocchio is quite strange: a wooden boy, counseled by a cricket, is repeatedly seduced by temptation and eventually swallowed by a whale. Oh, and there is the whole nose-elongation-in-response-to-untruths thing. Additionally, being early Disney—the Disney that shot Bambi’s mother and caged Dumbo’s—the movie does not shy away from nightmare-inducing imagery, particularly the trip to Pleasure Island and the coachman who brings the boys there (and takes them away as donkeys).

The movie starts with the song that became Disney’s theme: “When You Wish Upon a Star.” This song is the height of self-focused magical thinking, declaring that when you perform the titular action, “anything your heart desires will come to you” and that “if your heart is in your dream, no request is too extreme.”

Jiminy Cricket even begins the movie by citing the following story as evidence that dreams do come true. With a start like this, the viewer is primed for an inward-focused movie urging us to be ourselves by following our dreams. … But this is not what happens.

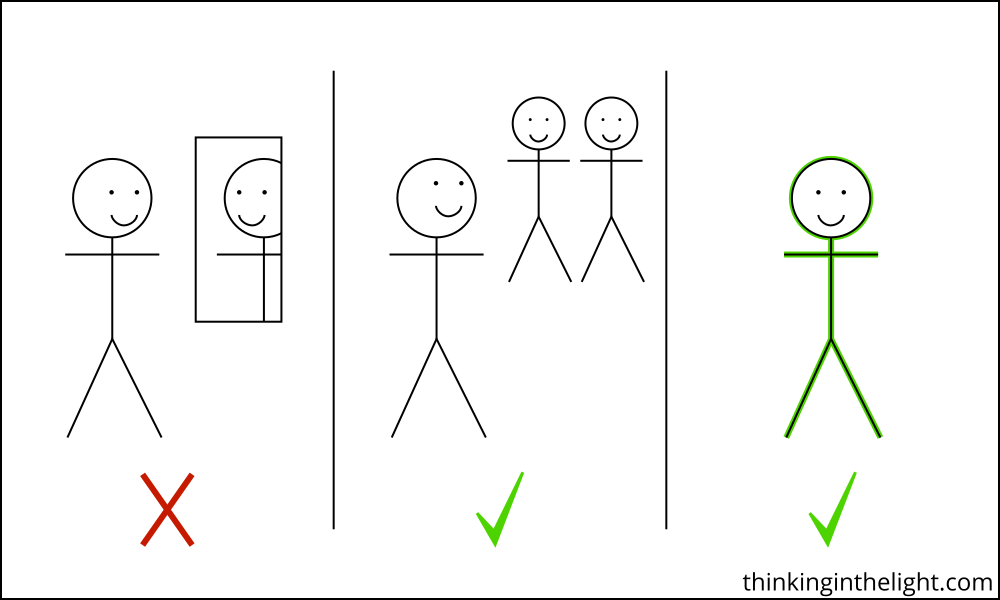

Instead, Pinocchio looks outward in two ways. First, while identity is central to the story, it focuses not on what Pinocchio is currently, but on what he is striving to become. He starts off a regular wooden puppet, but Geppetto the toymaker wishes that he would be a real boy. The Blue Fairy comes and grants Geppetto’s wish in part, bringing Pinocchio to life. He is not made a boy right away, however, which sets up the arc of the story: becoming a real boy is Pinocchio’s goal. The identity that drives him, then, is not what he is but what he is striving to be. He does not say, “I am a puppet, so I will be content with that and do puppetish things,” but he does what he does in order to achieve his goal of boyhood.

Second, the way he will reach his goal is also looking outward. He is not going to listen to his inner voice, but he will become a real boy by learning to do what is right. He will not follow his heart, but he will let his conscience be his guide.

Now, one might object that sometimes the conscience is called the inner voice, so how is following his conscience looking outward? On the one hand, Pinocchio’s conscience is literally external. Jiminy Cricket plays this role, being officially dubbed Pinocchio’s conscience by the Blue Fairy.

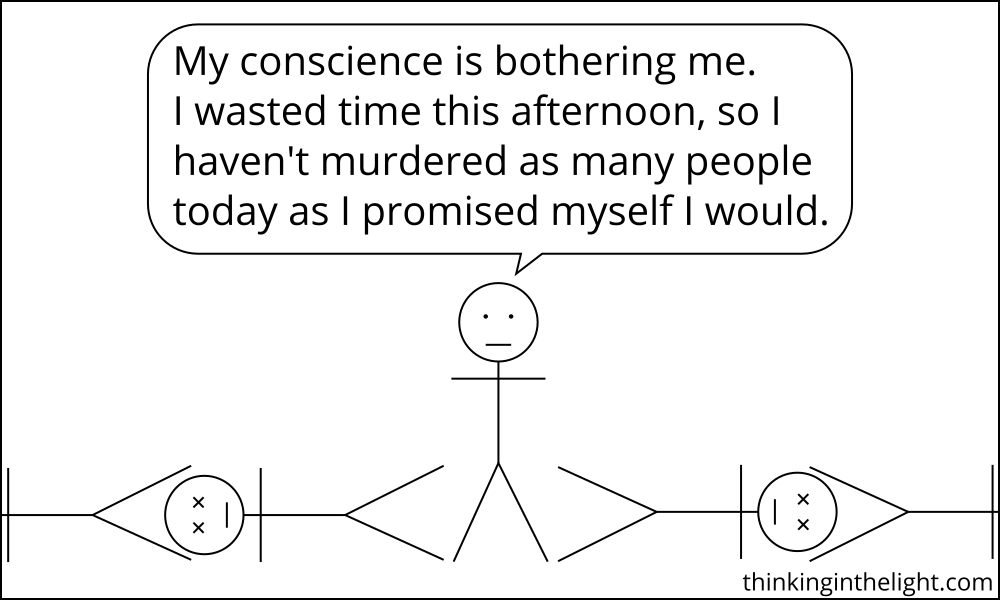

And more than this, even when the conscience is properly internal to the mind, its role as envisioned in Pinocchio is still to point me to something outside myself. Under any conception of the conscience, it is something separate from my desires (what I want) and my will (what I do). It can oppose both, or as Jiminy Cricket says, “A conscience is that still, small voice that people won’t listen to.” It tells me not what I want or what I do, but what I should do.

Separating conscience from my desires and will could still be compatible with seeing it as pointing to something internal to me. One conception of the conscience is to see it as the personal standards I have adopted for myself.

But this is not Pinocchio‘s vision of the conscience. It sees the conscience as pointing me outside myself to the objective standards of morality. As the Blue Fairy describes Jiminy Cricket’s role, he is to be “lord high keeper of the knowledge of right and wrong, counselor in moments of temptation, and guide along the straight and narrow path.” In order to become a real boy, Pinocchio must have first withstood the temptations appealing to his desires and shown instead that he is “brave, truthful, and unselfish.”

So, given that Pinocchio’s conscience is both speaking and pointing externally, if we are to discuss an inner voice in the context of the movie, what would it be? Pinocchio is so innocent and naïve that he doesn’t really have much of an internal life. This is part of the story, since it is dramatizing both his conscience and his temptations as characters external to him. Probably the closest he comes to expressing his inner thoughts is when he’s on Pleasure Island and declares that “being bad’s a lot of fun.” The story of Pleasure Island, where boys can fight, smoke, and play pool, clearly paints the impulses to do these things as bad. As the evil coachman states, “Give a bad boy enough rope, and he’ll soon make a jackass of himself.” Pinocchio and the other boys should not be listening to the inner voice of desire, but they should follow what is right instead.

Pinocchio eventually learns his lesson, and when Geppetto is swallowed by the whale Monstro, he goes in search of him. He rescues him from the whale, including staying with Geppetto after being told to leave him behind and save himself. The rescue is successful, but Pinocchio dies in the process. However, for his bravery and unselfishness, the Blue Fairy brings him back to life, this time no longer as a puppet. As Pinocchio realizes that he has finally reached his goal, he declares, “I’m a real boy!”

When it comes to identity, then, Pinocchio sets up the following order: 1) Don’t act on what I find within myself. 2) Instead, do what is right, including serving others. 3) By focusing on others and what is right, I will be rewarded by becoming the person I want to be, the identity I am striving for.

This is an attractive account of identity. It fits with an account of virtuous living as the goal of life, such as the one offered by Aristotle. For him, the sort of life we want to have is one where we have virtue and are displaying it. None of us start off virtuous by nature, so we must work at obtaining virtue through the constant practice of virtuous actions. Eventually our actions will not be prompted by an external set of rules we are following, but they will flow from a state within us. We will have become the virtuous person we were striving to be.

Similarly, from a Christian perspective I start off as a sinful person, one whose heart is inclined toward selfishness rather than toward what is right. So, I shouldn’t just do what my heart says, but I need to consciously strive to conform my life to God’s standards. I will still be a sinner throughout my life, one who does not always live up to the standards of righteousness, but God has promised to renew my heart in the next life and give me the righteousness I seek. Even now, then, my identity is found in what I will be, not what I am. I am guided by this vision of my new self.

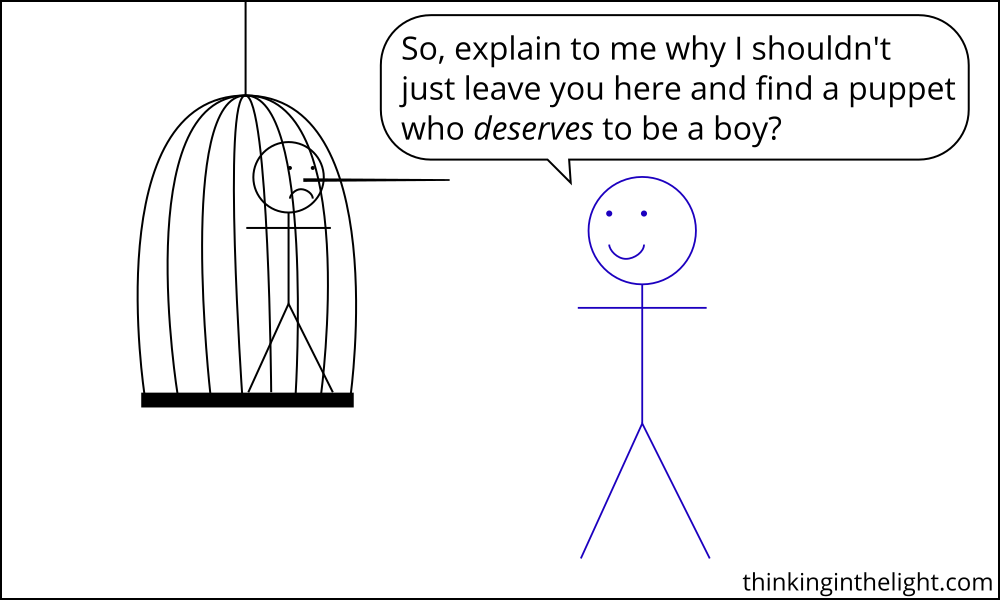

Of course, there is also a way that the message of Pinocchio differs from the Biblical view: it is fundamentally moralistic. Right from the beginning of his life, the Blue Fairy makes it clear that Pinocchio must earn his boyhood by being good. “To make Geppetto’s wish come true will be entirely up to you. … Prove yourself brave, truthful, and unselfish, and someday you will be a real boy.” Later, after Pinocchio pursues wealth and fame instead of goodness, ending up in a cage as a result, the Blue Fairy returns. She helps him but says it is the last time she can do so. She also accompanies her aid with a trite moralism: “I’ll forgive you this once, but remember, a boy who won’t be good might just as well be made of wood.”

Now, I recognize that when it comes to children’s stories there is a certain amount of simplification that must occur, and encouraging kids to do the right thing is not bad. It is also the case that in the Bible what we do is not irrelevant to our outcome in life. However, as someone who is relying on the grace of God—on the Bible’s central promise that it is God who saves us from the biggest consequence of our wrongdoing, not we who save ourselves—I find it disappointing to have the supernatural figure be a nag rather than a comforter.

And setting aside this issue, one could wonder about another aspect of Pinocchio‘s message. What does it mean to look to an external, objective morality, and how does such a morality exist? This is a good question to ask and one that has received many answers. One could, for example appeal to a utilitarian or Kantian explanation of morality, although I find each of these problematic. I will not address this question further now, but I do plan to address it more in a future post in this series.

In the next post, however, I am going to look at the other end of the spectrum from Pinocchio when it comes to thinking about identity and the inner voice. Pinocchio may listen to Jiminy Cricket, but when Moana sails the oceans she will learn to turn inward.

Share this post or sign up for future posts:

Bibliography:

- Pinocchio. Walt Disney Animation Studios, 1940.