Russell on Defying Death

Part 4 of the series Shuffled Off (Thinking about Death)

Stop, for a moment, and put on your thinking cap. Let’s enter the world of philosophy and conduct a thought experiment. In doing so, I want you to entertain the following idea: What if death is something bad?

“What if?!” you respond. “Isn’t death obviously bad?”

Ah, but actually this isn’t obvious to everyone. This series has so far looked at three different philosophers who would all say it is not something bad.

To which you reply, “Maybe philosophy is not all that helpful after all. I’ll go do something more productive with my time, such as scrolling through cat memes.”

But wait! Before you go, let me point out that this post is different. I will finally be looking at a thinker who agrees with you and thinks that death is bad. It is the end that destroys everything good we could possibly have. And though it is inevitable, it is an evil he thinks we should defy.

Hamlet also speaks of defying or resisting the bad things in life. In his soliloquy, he considers whether or not he should make war against the difficulties of life by killing himself and removing himself from their power.

To be, or not to be, that is the question:

Hamlet, Act III, Scene I

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And by opposing end them?

Hamlet decides against this course of defiance, as he goes on to explain. Suicide may take care of many problems, but it leaves a big one—death itself. What do we do, then, if death is our greatest problem? Are we helplessly at its mercy, or can we fight even this evil?

Bertrand Russell exhorts us to take up our arms in rebellion. Russell was one of the most well-known philosophers of the twentieth century, in part because he wrote not only technical works for other philosophers but also popular ones aimed at the general public. In the latter, he argued for such varied causes as ending nuclear war, the benefits of philosophy, and the truth of an atheistic, scientific viewpoint over a religious one.

It is in an essay of this last sort that he discusses death. He begins the essay, “A Free Man’s Worship,” with a story about God creating the universe and human beings. Those humans suffer and try to find meaning in the suffering (a meaning that isn’t there), only to have God destroy the whole thing in the end. After telling this depressing story, Russell declares that, in reality, things are even worse than this.

Such, in outline, but even more purposeless, more void of meaning, is the world which Science presents for our belief. Amid such a world, if anywhere, our ideals henceforward must find a home. That Man is the product of causes which had no prevision of the end they were achieving; that his origin, his growth, his hopes and fears, his loves and his beliefs, are but the outcome of accidental collocations of atoms; that no fire, no heroism, no intensity of thought and feeling, can preserve an individual life beyond the grave; that all the labours of the ages, all the devotion, all the inspiration, all the noonday brightness of human genius, are destined to extinction in the vast death of the solar system, and that the whole temple of Man’s achievement must inevitably be buried beneath the débris of a universe in ruins—all these things, if not quite beyond dispute, are yet so nearly certain, that no philosophy which rejects them can hope to stand.

Russell, “A Free Man’s Worship”

God is not a part of this picture. Instead, it is thoroughly materialistic, with nothing existing but various arrangements of matter. And in this scientific picture, death is the end of everything, so it is something very bad.

If Russell is right, it might sound like there is nothing for us to do but wallow in our misery. (Or maybe have ice cream for dinner again.)

This is not what Russell does, however. (Actually, I do not know his position on ice cream.)

He starts, like the stoics, by asking us to give up desires that cannot be fulfilled in light of the inevitability of death, to “no longer ask of life that it shall yield… any of those personal goods that are subject to the mutations of Time.” It is wisdom to recognize there are many things that fate and death will withhold from us.

To every man comes, sooner or later, the great renunciation. For the young, there is nothing unattainable; a good thing desired with the whole force of a passionate will, and yet impossible, is to them not credible. Yet, by death, by illness, by poverty, or by the voice of duty, we must learn, each one of us, that the world was not made for us, and that, however beautiful may be the things we crave, Fate may nevertheless forbid them. It is the part of courage, when misfortune comes, to bear without repining the ruin of our hopes, to turn away our thoughts from vain regrets. This degree of submission to Power is not only just and right: it is the very gate of wisdom.

Russell, “A Free Man’s Worship”

But Russell is not a complete stoic, and he only submits this far to the power of nature. His main message is that there is a way to fight back.

The weapons we have are our thoughts. These thoughts won’t change the fact of death—that is impossible, and trying to rebel in this way would be foolish. But we can use our thoughts to creatively take the raw, meaningless materials of nature and fashion something new, something beautiful.

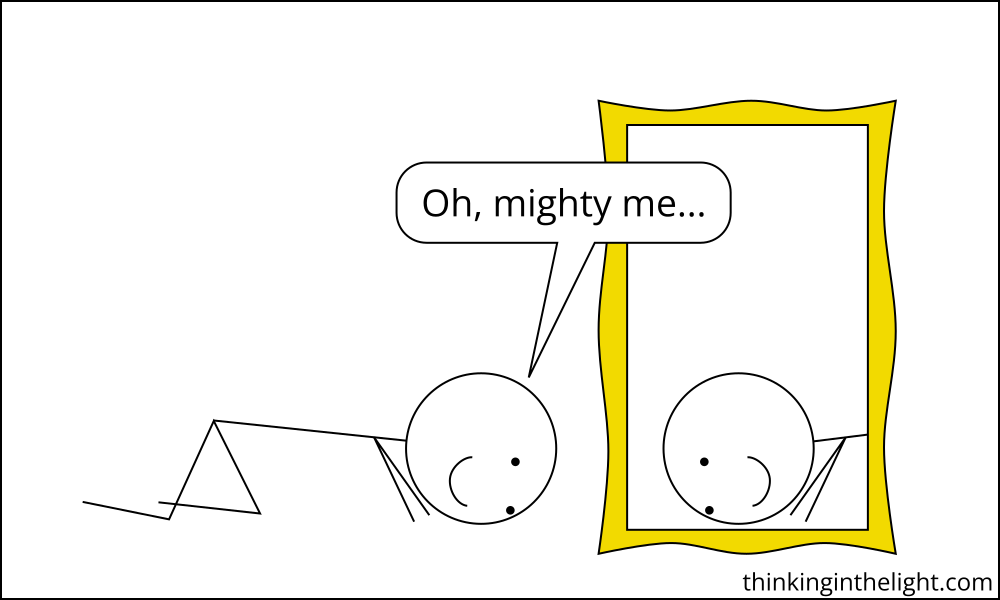

When, without the bitterness of impotent rebellion, we have learnt both to resign ourselves to the outward rules of Fate and to recognise that the non-human world is unworthy of our worship, it becomes possible at last so to transform and refashion the unconscious universe, so to transmute it in the crucible of imagination, that a new image of shining gold replaces the old idol of clay. In all the multiform facts of the world—in the visual shapes of trees and mountains and clouds, in the events of the life of man, even in the very omnipotence of Death—the insight of creative idealism can find the reflection of a beauty which its own thoughts first made. In this way mind asserts its subtle mastery over the thoughtless forces of Nature.

Russell, “A Free Man’s Worship”

Beauty is not something we find in nature, according to Russell. It is something we create ourselves and then apply to it. The world is a set of cold, hard facts, but we can elevate them into something with meaning.

Russell’s key example is tragedy. There is nothing beautiful about death and misfortune as they exist in the world. If I suffer and die due to fate and my own folly, I don’t lie on my deathbed and contemplate the beauty of the experience. (At least, I don’t think I do, and that is one scenario I’m perfectly happy to leave as a thought experiment.) However, if you give those same raw materials to a storyteller, they can weave them together into a beautiful tragedy. Hamlet is a good example. Almost everyone in it dies—whoops, spoiler alert—but nevertheless we’ve been reading and watching it for hundreds of years, because Shakespeare has crafted the unsavory elements into a story with depth, meaning, and beauty.

By taking elements from nature and using them for our own purpose—a purpose over which nature has no say—we are elevating something above nature. This makes it so we are not nature’s slaves, but there is something higher to bow to, something that is wholly ours. As Russell puts it, we defy nature by worshipping what we have created ourselves.

Brief and powerless is Man’s life; on him and all his race the slow, sure doom falls pitiless and dark. Blind to good and evil, reckless of destruction, omnipotent matter rolls on its relentless way; for Man, condemned to-day to lose his dearest, to-morrow himself to pass through the gate of darkness, it remains only to cherish, ere yet the blow falls, the lofty thoughts that ennoble his little day; disdaining the coward terrors of the slave of Fate, to worship at the shrine that his own hands have built; undismayed by the empire of chance, to preserve a mind free from the wanton tyranny that rules his outward life; proudly defiant of the irresistible forces that tolerate, for a moment, his knowledge and his condemnation, to sustain alone, a weary but unyielding Atlas, the world that his own ideals have fashioned despite the trampling march of unconscious power.

Russell, “A Free Man’s Worship”

By focusing on our own creating, free from the constraints of nature, we have, as Russell puts it in his title, a free man’s worship.

This freedom includes an overthrow of the tyranny of death. Yes, we will still die, but we will not bow to death and let it rule us while we live. We will make death serve our purposes—as in tragedy—rather than serving it.

The life of Man, viewed outwardly, is but a small thing in comparison with the forces of Nature. The slave is doomed to worship Time and Fate and Death, because they are greater than anything he finds in himself, and because all his thoughts are of things which they devour. But, great as they are, to think of them greatly, to feel their passionless splendour, is greater still. And such thought makes us free men; we no longer bow before the inevitable in Oriental subjection, but we absorb it, and make it a part of ourselves. To abandon the struggle for private happiness, to expel all eagerness of temporary desire, to burn with passion for eternal things—this is emancipation, and this is the free man’s worship.

Russell, “A Free Man’s Worship”

We make death serve us and are free from it.

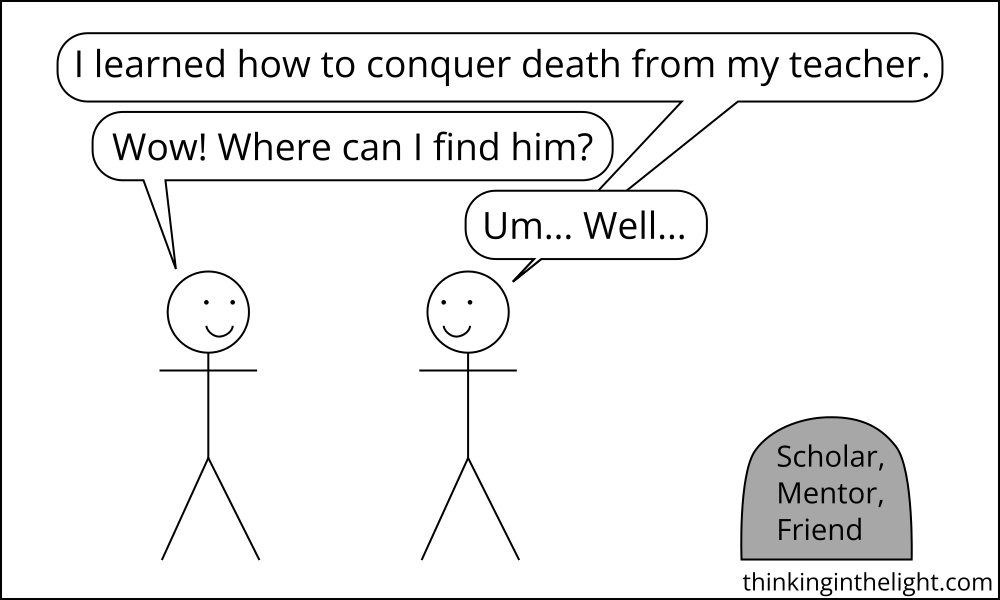

Or are we? This might sound empowering, but the fact is that Russell is still dead, and so will I be one day. Does thinking about death this way really help?

As I’ve been discussing throughout this series, the series was prompted by my dad’s death a couple of years ago. If I listen to Russell, perhaps I should turn his life into a story. Given my dad’s love of film, it would definitely have to be turned into a movie—perhaps he could be played by Tom Cruise. In the story, I couldn’t change the ending, since we cannot change death. But I could memorialize his feats in life and the way that these feats tragically and defiantly stared death in the face.

This feels inadequate somehow, but maybe it is a case of doing the best with what you’ve got. If life throws you lemons, make lemonade. Death is bad, and it is something we can’t avoid, so we make use of what we have—our mind—to bring something good out of it. We are like the prisoner in solitary who sings to himself, since it is the most human thing he can do in the face of a situation that is close to erasing his humanity.

On the other hand, this sounds an awful lot like being in denial. If the lemons life throws are poisonous, adding sugar and water is not going to help. Whether Russell’s position is helpful or a form of denial depends on how much contact it has with reality. And when looking at his picture as a whole, it turns out it is not much. This is because, given his presuppositions, the freedom he advocates for can’t actually exist.

Russell is trying to carve out a space where nature can’t touch us, where we can be free. But in light of his overall picture, it cannot be the case that we are really free. As a materialist, he has to say that there is no part of us that is not ultimately due to natural forces. There is no non-material soul, and the ideals we create with our material brains are both due to that material, and, insofar as they speak about things that are immaterial, they are totally imaginary. It is true that when we are thinking about these ideals we are not directly thinking about nature. But neither are we thinking of anything real, and those thoughts are just as due to nature as everything else. Even our resistance to nature—the resistance Russell champions—is ultimately a manifestation of it.

Since the freedom isn’t real, and neither are the things we are thinking about in our supposed freedom, to rely upon our free minds as a source of comfort in the cold, death-filled world is a form of escapism. It is telling a story and believing a lie as a way to distract ourselves from the truth. We are not like the prisoner singing to himself, for he has found within himself a piece of humanity the jailers cannot touch. Instead, we are sitting in the cold cell pretending it is a warm, sandy beach, an activity that is ultimately due to the influence of the jailers.

Perhaps, however, this falsehood does not bother Russell, for he describes our situation not in terms of belief, but in terms of worship. He presents us with two options: we can worship and fear uncaring nature, or we can worship the ideas we make. So even if those ideas are false, at least we are not bowing to nature.

But why would I worship a lie? One possible answer is that the lie is mine. In worshiping the ideal I created, I am implicitly worshiping myself.

Now, I am perfectly content to be the object of worship—the world is so much nicer when I am the center of things—but the fact is that bowing to myself is still living a lie. A whopper of a lie. I can pretend that I am somehow transcending nature, but in reality, we are weak, insignificant nothings in the face of it. There is a reason that polytheists worship the gods of nature. They recognize that when it comes to a contest between me and nature, it is an ant with a toothpick battling a herd of elephants armed with nuclear weapons. If my worship is going to be any sort of recognition of the powers in the universe, and if my only options are to worship myself or nature, there is no question as to what to do.

But even in light of this, Russell’s position still has an attraction. Maybe I don’t care about the truth and I don’t really care about worshiping. Maybe I just want to feel better. Why not live with pretty falsehoods when the alternative is a bleak truth? On the one hand, there is no definitive answer to counter such a position. If I want something and am not interested in the truth regarding it, there is not much to say to me. I will do what I want.

On the other hand, it is worth pointing out that to live this way is to live like an addict. By saying this, I don’t mean that there is something on which I am chemically dependent. Rather, just as the addict uses something—drugs, alcohol, sex, food—to try to make themselves feel better, even if they know it is only causing more harm, so too in this case, it is using a thing—a false picture of the world—to push away uncomfortable realities. It is the ant closing her eyes and humming a happy tune while the elephants stomp around her and she breathes in radioactive fumes.

This sort of distraction has an attraction I certainly recognize. When discomfort or distress is overwhelming, I want to escape that discomfort, and it feels like any necessary means are worth it. And what is more distressing than death? The pain of losing my dad is one of the deepest I’ve felt, and if Russell is right about death being oblivion—if I think that all I have is a few years here of striving against an unconquerable nature, followed by a permanent erasing of everything I am—then my own death is horrific. If it is a fate I cannot escape, at least I can try to escape the thought of it. That is a position I understand.

But is it one I want to embrace? Do I want to live my life like an intellectual alcoholic, numbing myself to the pain by constantly drinking down lies? If I recognize that alcoholism is not a life worth choosing, then I shouldn’t strive to become a fantasyoholic either. Even if the world is as bleak as Russell says, the better life is the one that faces the truth head-on.

And when I commit myself to the truth, I recognize an unexpected benefit. I open myself up to hope. Because maybe Russell is wrong about the world. Maybe he is overstating things when he declares that the meaninglessness of our lives and deaths are “so nearly certain, that no philosophy which rejects them can hope to stand.” If he is wrong, and there are ideals that exist in the world independent of us—ideals we didn’t create but by which we can live and in which we can find meaning—then this changes everything. Depending upon what those eternal truths are, it could even change how we think about death.

But if I adopt a numbing falsehood in order to avoid the truth, I will never know.

In fact, I do think that Russell is wrong. The world does have meaning, and even death will not destroy this. The terrible destroyer will not have the last word. And in the next post I will examine why.

Share this post or sign up for future posts:

Bibliography:

- Russell, Bertrand. “A Free Man’s Worship.” [1903.] Collected in Mysticism and Logic and Other Essays. George Allen & Unwin LTD, 1917. Digitized edition from Project Gutenberg: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/25447/25447-h/25447-h.htm#III

- Shakespeare, William. Hamlet. [c. 1601.] Digitized edition from Project Gutenberg: www.gutenberg.org/files/1524/1524-h/1524-h.htm