Stoic Apathy Towards Death

Part 2 of the series Shuffled Off (Thinking about Death)

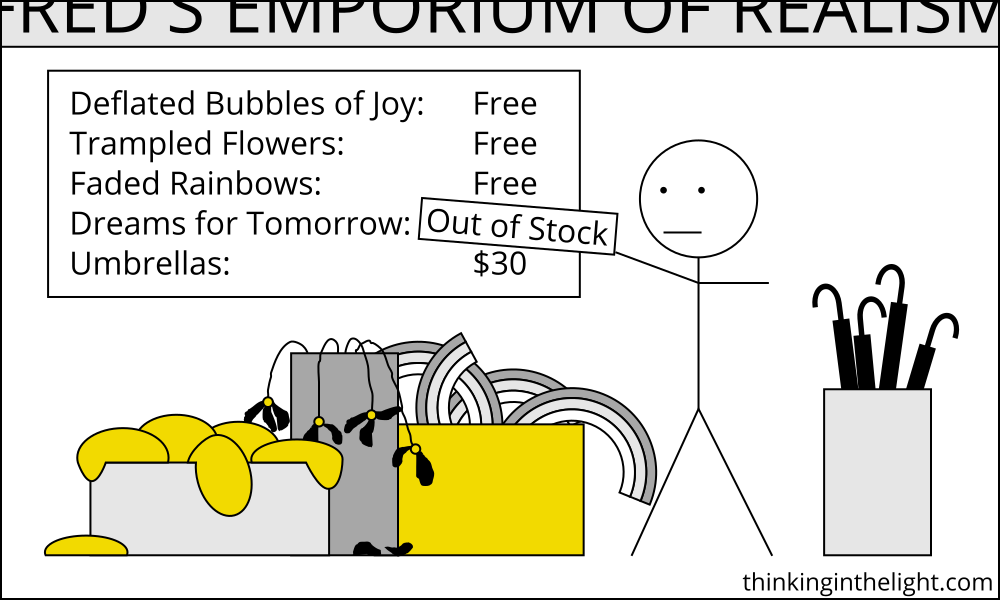

Everything in life is completely wonderful. Our everyday lives are filled with rainbow after magic rainbow, with never a cloud in sight. The main sentiment we feel in life is joy—a joyful, joyous joy bubbling up within us as we waltz through the flowers of our existence.

Of course, we all know this is nonsense.

Hamlet, for one, knows this isn’t the case, and in his famous “To be or not to be” speech he cites the difficulties of life as the main reason to consider leaving it.

For who would bear the whips and scorns of time,

Hamlet, Act III, Scene I

The oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely,

The pangs of dispriz’d love, the law’s delay,

The insolence of office, and the spurns

That patient merit of the unworthy takes,

When he himself might his quietus make

With a bare bodkin?

Why, Hamlet asks, shouldn’t we take a dagger (a bodkin) and settle our accounts (make quietus) by killing ourselves, given all the miseries he lists? And even if his solution is problematic, he isn’t wrong about the list: life brings all these hardships and more. Oppression, insults, the vagaries of time, being let down by the law and by love—he doesn’t even mention when your phone battery dies and you don’t have the charger! Earlier in the speech Hamlet summarized these hardships as “the heart-ache, and the thousand natural shocks that flesh is heir to.” By virtue of being human, we are prone to suffering in myriad ways.

Among these ways, however, one stands out. Injustice, suffering, and disappointment are all difficult, but perhaps our greatest suffering comes from another source: the pain that comes when those around us die. We grow close to people. They become part of our lives. Then they are ripped away, leaving a gaping hole. Of the thousand natural shocks that we experience, surely death is one of the greatest.

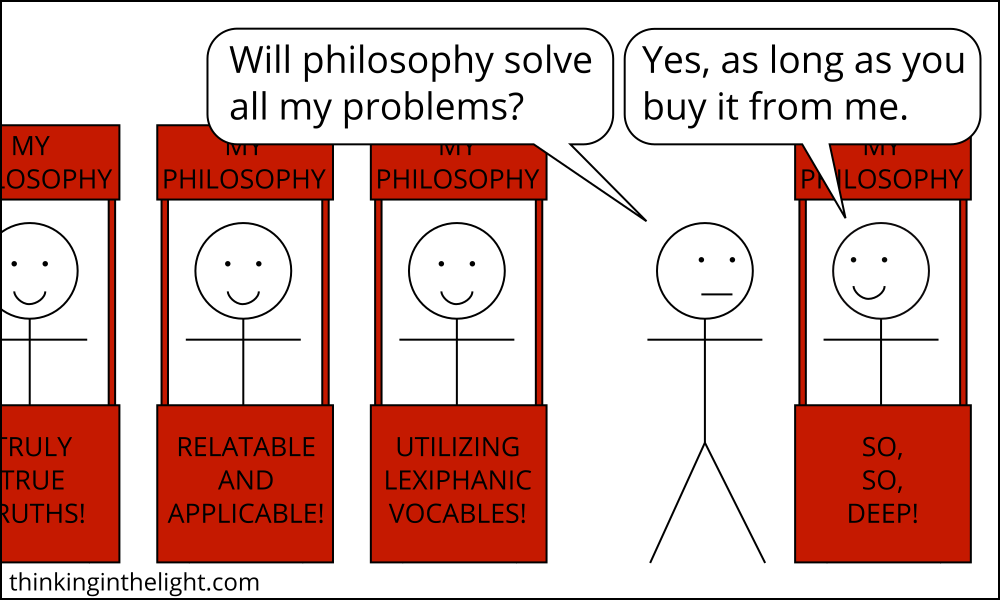

But what if life didn’t have to be difficult? Some say it doesn’t, including the philosopher Epictetus. He wouldn’t say that everything in life is wonderful, but he would also argue against Hamlet that it is bad. He would say this even when it comes to death. This is not because he was unacquainted with death and hardship. He lived a long time ago, during the Roman period, when the relative lack of medical technology meant that, compared to today, more people died. (Well, more people died younger—both then and now the percentage of people who die eventually is 100.) And when it comes to hardship, he spent the first part of his life a slave and the last part lame. Epictetus says that if we look at situations like these from the right perspective, however, we don’t need to find them difficult. The perspective we must adopt is that of the stoic.

The goal of stoicism is to help us have a good life—a life of tranquility. Many things in our experience disturb us, but a stoic like Epictetus declares that this disturbance is not inevitable. When I am disturbed, it is not due to my circumstances but due to the way I think about them. And how I think about the world is in my control. This means that I can control whether or not I am tranquil.

He says this is true even in the face of death.

It isn’t the things themselves that disturb people, but the judgments that they form about them. Death, for instance, is nothing terrible, or else it would have seemed so to Socrates too; no, it is in the judgment that death is terrible that the terror lies. So accordingly, whenever we’re impeded, disturbed, or distressed, we should never blame anyone else, but only ourselves, that is to say, our judgments.

Epictetus, Handbook 5

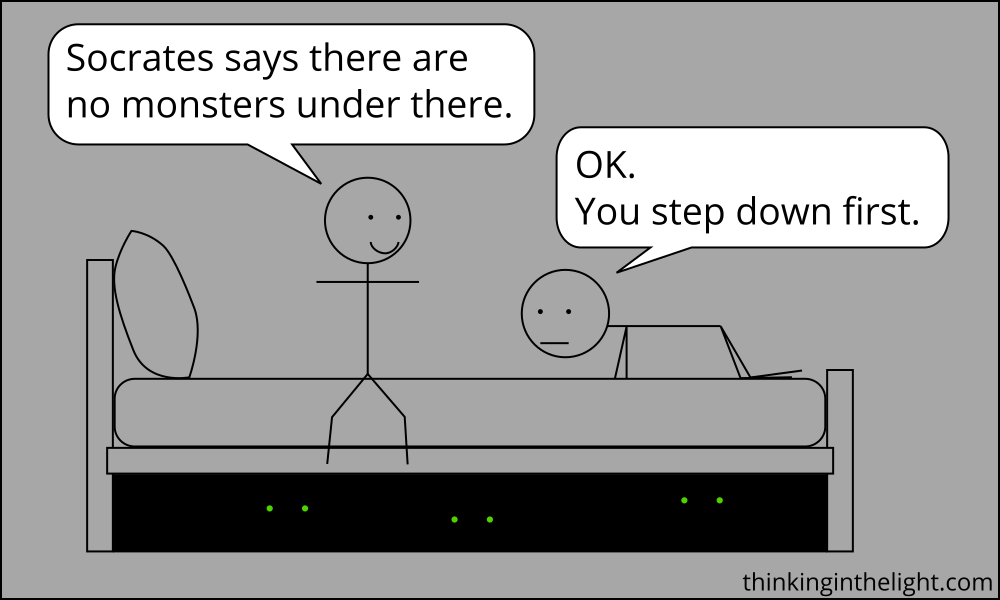

Socrates was famous for not caring about whether he died, but only about whether he acted rightly. He did not see death as something bad, so he was not disturbed by it. If there had been something intrinsically bad about death, Socrates was a smart guy and would have realized it. So why, then, are we afraid of it?

Now, bringing in Socrates leads the discussion in the same direction I focused on in the previous post on Epicurus: Is my own death bad? Epictetus the stoic would agree with the answer given there by Epicurus (no) although he would give different reasoning for it. However, here I would like to focus on the aspect of death mentioned above: the hardship of the death of a loved one.

Epictetus is equally clear in this case. We should not be disturbed by the deaths of those around us. To be disturbed would be to give up tranquility voluntarily. It is in my control and I can have it if I want it. And if he is right, if he is able to take the most upsetting thing in life—the death of a loved one—and then explain how we can avoid that upset, how we can have tranquility even here, then maybe stoicism is on to something.

In order to make his case, Epictetus points out that we react differently to the death of someone close and the death of someone we don’t know.

The will of nature may be learned from those events in life in which we don’t differ from one another. … Someone else’s child or wife has died; there isn’t anyone who wouldn’t say, ‘Such is our human lot.’ And yet when one’s own child or wife dies, one cries out at once, ‘Oh poor wretch that I am.’ But we ought to remember how we feel when we hear that the same thing has happened to others.

Epictetus, Handbook 26

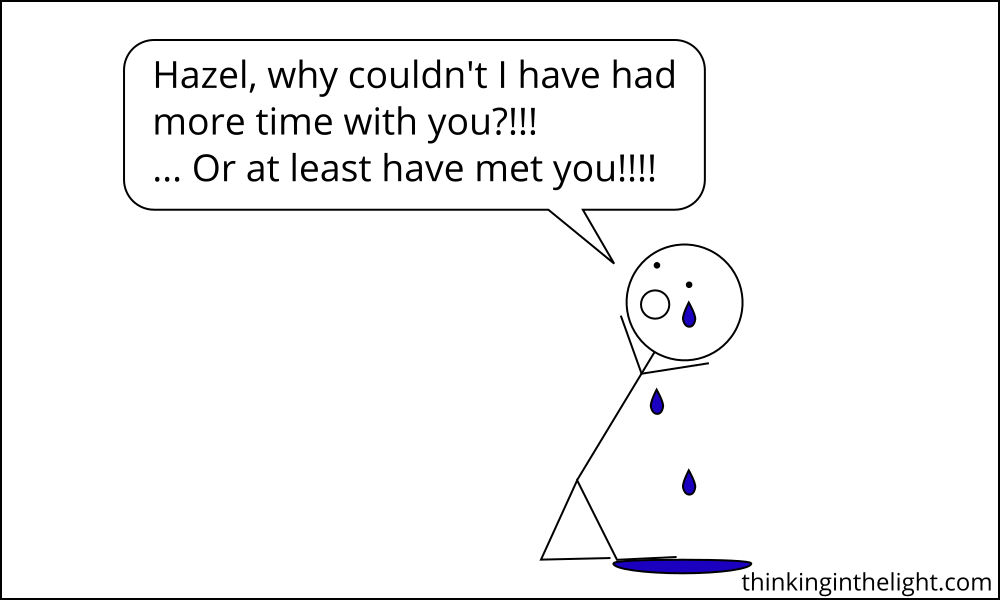

Suppose that you travel to a town you have never visited. You are there on a sightseeing trip, and you don’t know anyone who lives there. You open up the local paper (it is a quaint town that still has such a thing) and happen to find the obituaries. There you see that five people have died in the last weeks, all in their 80s or 90s, including a woman named Hazel Bennington. What is your reaction? Do you cry out, “Not Hazel Bennington!” and burst into tears? Do you become overwhelmed by the loss of these five unique individuals who will never again bless this earth with their presence?

No, most likely you do not. Probably you don’t think about their deaths at all, or at the most the thought flickers across your mind, “Oh look, people died.” Hazel looks about the same as every other 89-year-old woman of whom you have ever seen a picture, and when you flip to the next page and start reading about the pigeon infestation in the park, you have already forgotten her.

Our experience almost all the time is to think of a human death as an ordinary event, akin to gravity or Tom Brady winning the Super Bowl. We only get upset—see the death as something bad—when our emotions get involved due to a personal connection. Since this is the case, Epictetus would like us to consider which is likely to be the truer account of reality: the one that only occurs to us in those rare times that death touches us, or the reaction that happens 99.9% of the time.

If he is right, if we are just overreacting when death comes close, then the solution to our pain is apathy. Literally, the word “apathy” means having no emotion, and this solves the problem according to Epictetus: remove the emotion and treat those to whom we are most closely connected just like everyone else.

With regard to everything that is a source of delight to you, or is useful to you, or of which you are fond, remember to keep telling yourself what kind of thing it is, starting with the most insignificant. If you’re fond of a jug, say, ‘This is a jug that I’m fond of,’ and then, if it gets broken, you won’t be upset. If you kiss your child or your wife, say to yourself that it is a human being that you’re kissing; and then, if one of them should die, you won’t be upset.

Epictetus, Handbook 3

If in every interaction with my child I am thinking, “This is my beloved, unique, irreplaceable child,” then of course I’m going to be upset when he dies. But if I think of him as simply a human being—of which there are many and for which death is a regular, normal event—then I will be tranquil even if he dies. His death is simply like those I read about in the obituaries.

So, according to Epictetus, I can be free from the pain of death. All I need is apathy. When I rightly consider the deaths of those around me, I just need to recognize that they are not bad, and they won’t upset me.

Someone might object here that stoicism is just stuffing our emotions, and that doing so is not healthy. In response to this, Epictetus would acknowledge that he is trying to remove these emotional responses from our lives, but he would deny that doing so is to stuff them. ‘Stuffing’ implies that the emotions remain, but we try to bury them (probably unsuccessfully). In the view of Epictetus, however, we are making it so the emotions don’t exist in the first place. And we can do this, because we are recognizing the true nature of reality.

We are like toddlers screaming until we are red in the face because our sibling took the one cookie we wanted from the full plate of cookies that are identical. If we grasped the reality of the situation, we would not be stuffing down our feelings, but we would have no reason to be upset at all. For Epictetus, we must remember the reality that events in the world—such as death—are outside of our control and are in themselves neither good nor bad. What makes them good or bad are our thoughts about them, and these are in our control. So why would we adopt the false idea that the death of a loved one is horrible, when all this does is bring us needless pain?

If you want your children and wife and friends to live forever, you’re a fool, because you’re wanting things that aren’t within your power to be within your power, and things that aren’t your own to be your own.

Epictetus, Handbook 14

If Epictetus is right, he can spare us from a lot of pain. Because losing a loved one is painful. When my dad got sick and died, words like ‘sad’ were woefully inadequate to describe the situation. Rather, it felt like an earthquake ran through the ground of reality and I fell through the resulting fissure. Why go through that if I don’t have to?

For a Christian, there might be a further attraction towards stoicism, since Epictetus comes close to articulating a position that sounds deeply faithful. It is easy to say, in the face of a great loss, “This is part of God’s plan, so it is not sad.” Saying this is more than simply the view that God is in control of things, but is it saying that I should never be upset about what happens, because that is a kind of unbelief. As someone who believes in the sovereignty of God, I know that it is easy to think that it entails the stoic view. The similarity with Epictetus lies in the way this Christian stoicism seeks to change my view of reality, so that I no longer experience the pain.

But what if it is sad when people die? What if Epictetus is wrong in his reasoning and advice?

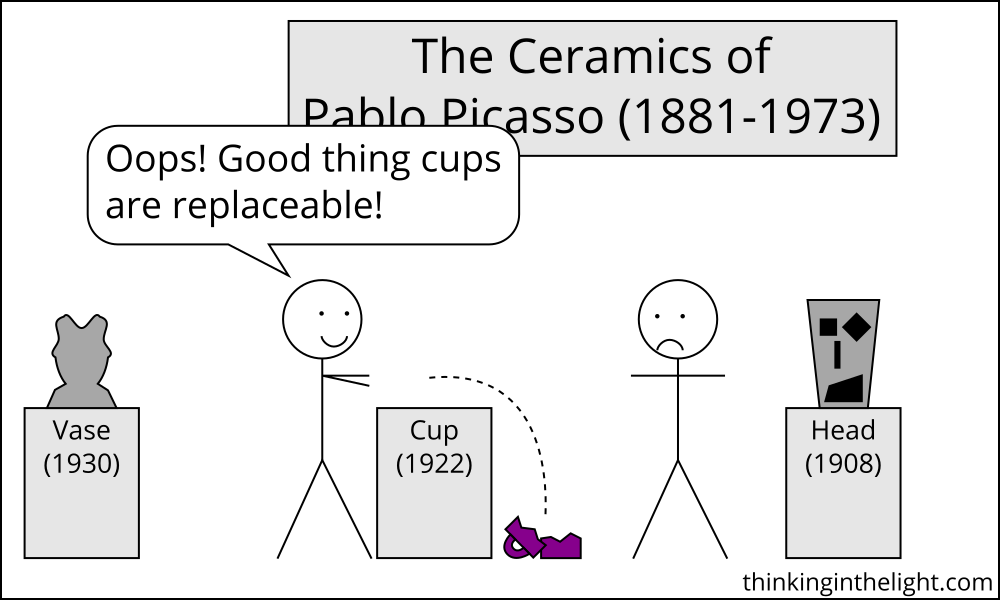

Epictetus advises me to think that people are replaceable the way drinking jugs are, so let’s think about my reaction when I break my cup. Why might I react? First, I might simply be upset because this is the cup I use every day. How will I wake up in the morning without my single-source, hand-poured Mountain Dew? The answer, of course, is that I get a new cup. As Epictetus says, one is as functional as another.

I might also be upset, because the cup reminded me of something. That is, I am sentimental towards it. Perhaps I got the cup on my childhood trip to Grover Cleveland’s birthplace. Or I received it as a promotion when I went to see Fantastic 4: Rise of the Silver Surfer. In these cases, I am projecting a value upon the cup, and it is legitimate to ask whether I should be doing so. If the cup does not have the value in itself, maybe I would be better off not upsetting myself by projecting onto it.

But sometimes I might be upset, not because of a value I am projecting, but because the cup has a value inherent to it. Maybe it is beautiful. Maybe it truly serves a function better than other cups. In these cases where I am recognizing the objective value of the cup, I could ask whether Epictetus is right, whether I will find an equivalent value in another cup, such that I don’t need to bother about the destruction of this one.

These reactions to cups are parallel to those I could have when it comes to the death of a person. I could be upset by someone’s death because they did something for me. If this is the case, then the person may be easily replaceable. I can always get a new butler or chauffeur. This is analogous to the first case of the cup above, and it seems like the primary case Epictetus is thinking of—it seems to me, however, to be comparatively rare.

What about the other two cases? When a person I love dies, am I projecting value or recognizing it?

First, it is worth noting that when I feel sentimental towards a person, it is usually different than it is with an object. With the cup, I see it and remember the trip or the movie. But when I feel sentimental upon seeing a person, I am most likely remembering the person and the activities we shared. That is, I have the feeling because I see value in having done the activity with the person, which is, in turn, seeing the person as having value. Of course, I suppose it is possible for me not to value the person and merely to have them remind me of something else, but that seems to particularly devalue the person. (And to just be weird.)

Next, when I see a person as having value, what does this mean? Sometimes this is really an observation about myself—it is saying that I know this person and enjoy them. In this case, Epictetus’s advice may apply. When one source of enjoyment dies, maybe I just need to meet another.

But it is also the case that I can recognize a value in humans that is inherent, that I am not merely noting my feelings but am recognizing something objectively there in the person. And there is a strange thing about inherent value in humans: in talking about something all humans have, it is really speaking of the unique value possessed by each. When I recognize and appreciate your value, it is both recognizing something you have insofar as you are a human, and something you have insofar as you are you. Humans are individually respectworthy as unique, not just as instances of humanity.

And if humans have value apart from my assigning it, then when a person dies it is not a neutral event. It is a bad one. The death of a person is the removal from the earth of a valuable being.

Further, if each person has a unique value, then Epictetus is wrong to suggest one person is replaceable by another. A death is an evil that can’t be compensated for.

And, if stoicism’s view of the world is incorrect, its advice for how to live in it is problematic. Epictetus advocates being apathetic and eliminating emotion, because the emotions don’t reflect reality—he says they treat as bad things that aren’t. But if he is wrong and the things are truly bad, then troubled emotions can be an appropriate response. Sadness makes sense when something with value disappears.

This means that the objection I considered earlier returns. It said that stoicism was just stuffing our emotions, and Epictetus responded that it was, instead, properly reflecting reality. But if stoicism has misconstrued reality, then it is ultimately making use of a false philosophy to stuff our emotions.

So, death is bad and something to mourn. To return to the particular case: my dad’s death is upsetting, and I shouldn’t see it otherwise. Maybe, just maybe, I should even weep when reading the obituaries. (I’m not entirely sure how to think about that last one yet.)

As a Christian, I want to make sure that I don’t make this same mistake as well, papering over the pain of death with a platitude about how everything is God’s plan. I will have more to say about a Christian view of death as this series progresses—in fact, the next post in the series will be another ancient philosopher whose position is easy to confuse for Christianity. And once again, he will be (sigh!) arguing that death is not something bad.

Share this post or sign up for future posts:

Bibliography:

- Epictetus. Discourses, Fragments, Handbook. Translated by Robin Hard. Oxford University Press, 2014. (The Handbook is a short summary of Epictetus’s philosophy, and it is worth reading if you are interested in thinking more about stoicism.)

- Shakespeare, William. Hamlet. [c. 1601.] Digitized edition from Project Gutenberg: www.gutenberg.org/files/1524/1524-h/1524-h.htm