I remember seeing Batman with my dad. It probably wasn’t the real Batman, since if I remember correctly it was at a mall in Oregon. The details are hazy, but I think we stood in a line and Batman walked down it and handed me a card with the bat symbol on it.

I more clearly remember my dad taking me to see Batman: Mask of the Phantasm. The first time we tried, we went to the wrong theater. We tried again the next day and got it right.

I remember doing lots of stuff with my dad. Some things were big events, like going to the hospital to visit my mom and baby sister. Or going to a concert and having to sit through an opening act neither of us liked, so we made fun of them to each other. Some of the things I remember were super ordinary, like shopping at the grocery store (I held the list) and going through the McDonald’s drive-thru (I had to give him a fry tax on the way home). We also did the typical father-son things, like watch movie adaptations of Jane Austen novels and walk around home show conventions trying to sound like HGTV hosts.

As is probably natural, due to all the things we’ve done together, my dad and I have a lot of the same interests: movies, music, books, etc. But as is also natural, we have different tastes and don’t always like the exact same things. If I had to summarize it, I would say that he has a higher interest in (and tolerance of) subtlety. He is lemon meringue pie, Debussy, and Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker, and I’m chocolate cake, U2, and Ridley Scott’s Gladiator.

Given our shared history and common interests, another way to put it is that my dad is my friend.

When I became a dad, this was the aspect of fatherhood that excited me most. I want to eat McDonald’s with my boys. I want to take them to cool places and see it as they realize how cool they are. I want to watch Star Wars movies with them. (We just did, and my oldest declared The Phantom Menace to be one of the best, so clearly they need fatherly guidance.) I want to share this world we live in.

But being a dad is not just about being a friend to one’s sons. It is also about teaching them.

My dad taught me many things. It’s true that playing baseball is not one of them. (Ball-throwing is not really his thing.) Nor did he teach me how to play the guitar. (My fault. He showed me three chords and said he’d teach me more when I learned those. I never did.) But he did teach me a few things about building shelves. He taught me algebra, geometry, calculus, computer programming, how to ask for a job application, and the proper order in which to read the Chronicles of Narnia. (Don’t even think about calling The Magician’s Nephew the first book!) Further, he is a Bible teacher, so I learned a lot from his talks, sermons, and writing—but especially from just talking to him around the house or on the phone. (It is handy to have a personal Bible reference service to call at a moment’s notice.)

However, what he really taught me was what things in life are important.

I remember him going to paint someone’s house when they needed help, and he took me along. I remember the time he took a man whom he did not know especially well to the hospital. I don’t remember first-hand but have heard many times about how, when I was a toddler, he had to hold me down while I screamed, so the doctor could stitch up my scalp. And then he took me back to the doctor to do it all over again when I fell and re-opened the wound.

And I remember those offhand comments he made to me from time to time. When I was in college I wrote a senior thesis on Bertrand Russell, a famously atheistic philosopher. I was talking to my dad enthusiastically about something Russell had written, and my dad pointed to my head and said, “Be careful what you put in here.” Now, I still think Russell is fundamentally right regarding the topic I was writing on—the definition of truth—but my dad’s exhortation stuck with me. It is important to think critically about the ideas one absorbs. I also remember a time he was sitting at his desk, preparing for a talk. He stopped to comment to me on the importance of listening to the Apostle Paul: “This is a man who talked to God.”

In general, he has always made it clear in his life how important God and the Bible are to him. This is not done by being super churchy. (The church I grew up in is among the more casual churches in existence.) And it is not by being unflappably optimistic in the face of life’s challenges. (No one has ever accused my dad of even flappable optimism.) I don’t even know that I can point to something in particular in support of my claim that his faith is clear. Perhaps it is the way he works at life. There will be things he would rather not do or that don’t fit his personality well—like taking someone to the hospital or holding down his screaming son—but he will do them because he sees them as the right thing to do. In these moments he makes it clear that he is not merely living for himself, but for God—that the words of the Bible are not merely his job, but he believes them. They are what shape his life.

This kind of teaching-through-living is easy to neglect now that I am a father. It is more fun to think about doing exciting activities with my sons, and more straightforward to think about the formal teaching I can do as they grow older.

But, scary as it is, a father’s legacy to his son is the life he led. The way my own dad lived is an important reason that I am who I am, including the fact that I am a Christian. Living beside him was at least as important as any formal lesson I was taught or any doctrine I learned.

This is not to say that learning through reading and thinking is unimportant (or I wouldn’t be doing this site). Nor is a father’s faith any guarantee that the son will also choose to trust God. The fact that I am a Christian is ultimately due to my own commitment and the work of God in my heart. And I should also point out that my dad was not the only exemplar I had to follow. I was blessed to grow up in a community filled with adults whose faith and lives were worth emulating. But while acknowledging all this, it is still the case that my dad’s life has taught me and shaped me in fundamental ways.

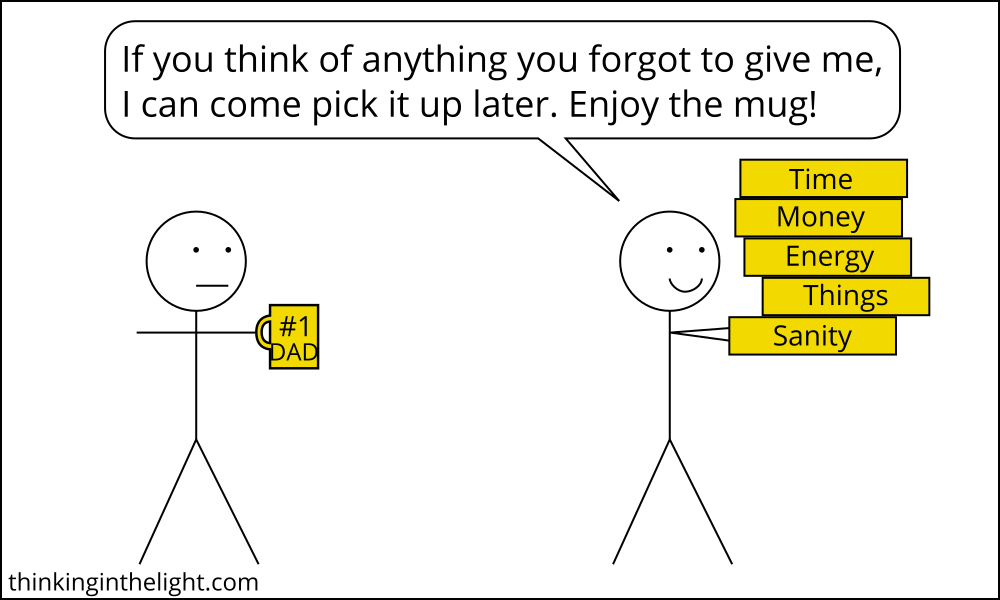

Like a typical son, I have taken the vast majority of what my dad has done for me for granted. (At least, it seems typical for a contemporary, western, individualistic, American son.) Even if it is normal, this still doesn’t reflect well on myself. My dad could have lived life for himself and screwed me up, but he didn’t. One would think he should get a trophy or a yacht for this, but I don’t think I even sent him anything this last father’s day.

On the other hand, my dad never gave the impression that he was doing it for the recognition. His life has been more about the “Well done, good and faithful servant” he will one day hear. This is only something he can get from his own Father, and it is really the only thing anyone can receive that matters. But in any case, for what it is worth: Dad, your son thinks you have done well, too.

I doubt that there is such a thing as a universal experience of the father-son relationship. In the past it was often expected that the son would simply take over his father’s profession—that in some ways he would become his dad. Once again, my experience has been shaped by western individualism, so I have made moves to differentiate myself, especially when I was younger. My dad has a beard, so I shave. He does theology, so I do philosophy. He wears clothes that make him look like my dad, and I wear different clothes so I don’t. However, as I’ve gotten older it has become clearer that, try as I might, this apple has not fallen very far from the tree. (After all, we are both teachers!) And as I’ve gotten older I’ve also come to be OK with this. I could do a lot worse than to become my dad. In fact, there are many ways in which I still hope to be like him.

It is hard to summarize a 40-year relationship in a single post. I haven’t even mentioned how I remember going to the beach or watching Joe Versus the Volcano. Or how I remember the way my dad treated my mom, an experience that taught me how to be married. And despite the standard way I write posts for this website, I’ve yet to bring in any philosophers discussing the nature of fatherhood. (In all honesty, personal relationships are not the forte of most famous philosophers.) Really, when it comes down to it, this whole post has been a long-winded way of saying: Dad, I love you, and I remember.

Share this post or sign up for future posts: